You think that I don’t even mean a single word I say,

it’s only words and words are all I have

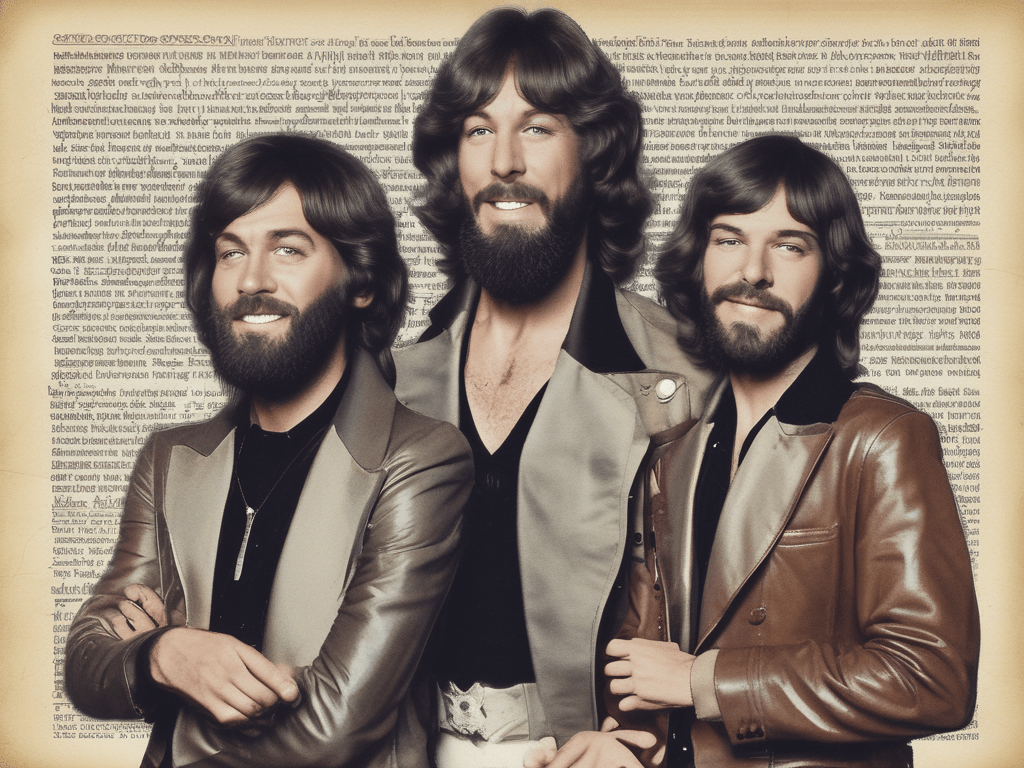

Bee Gees

Words are not equal. In the world of scripture, it is even possible to assert the word “equal” is not equal to itself!

In antiquity, perhaps due to the combination literacy rate, availability of writing materials, and oral tradition, the spoken word brought with it a sense of primacy. Despite the fact there was significant literacy in antiquity, spoken words were preferred to written words.

For example, letters were intended to be read out loud as opposed to a silent reading by the recipient. Scripture, as well, were words to be delivered for public consumption via the mouth, the voice. Additionally, in public life and commerce. in situations when reducing words to a medium was not plausible or possible, the spoken word was valued equivalent to a written legal document; an oral contract was as enforceable as a written one. Vow! Not wow! Words attached to vows-sworn on-carried tremendous weight.

In biblical times, making a vow- swearing upon the Lord’s name- was a way of elevating a word to something beyond a mere word. Arguably, the word became an “action” word.

In other words, something was guaranteed to or not to occur as a result of the vow being attached to the words. Thus, words under a vow were different from all other words. This differential is rooted in the Ten Commandments. Within the Decalogue, the Commandment not to use the Lord’s name in vain applied to vows.

The Torah Portion Matot contains a passage that elaborates upon the Ten Commandments with respect to vow making. Matot states: ” A man who will make a vow to the Lord or has sworn an other to make a restriction on himself shall not desecrate his word. He shall do it according to everything that comes out of his mouth.” Numbers 30:3.

This passage expands upon the Decalogue’s commandment. Exodus 20:7. While many Commandments provide the directions of “shall” and “shall not”, the Decalogue offers no information as to what is to be done if there is a breach. How is a violation to be adjudicated? How was the broken vow to be addressed?

Matot expands upon the Decalogue. In legal terms, the Torah Portion provides the “remedy” for the breach of a vow. It directs that the individual should “do it [the act] according to everything that comes out of his mouth” bear much similarity to a legal concept. The legal term applicable to this remedy is “specific performance”. “Specific performance” a type of equitable relief that requires a party to complete the terms of a contract.

The Matot portion goes further into the nature of vows. One particular passage of interest is that the vows of a youthful woman living in their father’s house allowed for the rescission of a vow. Numbers 30:4 [“If a woman makes a vow to the Lord, or imposes a prohibition [upon herself] while in her father’s house, in her youth”]

Per the Commentator Rashi, the dividing line between a youth and an adult was at 12 years of age. He indicated 12 1/2 years as the line while there are references to 12 years and one day. Thus, an individual’s capacity to make a vow was a matter of concern in antiquity. With this passage, it is likely that it related to marriage vows. It is worthy to appreciate that the age adulthood was viewed differently in antiquity.

In sum, perhaps the Bee Gees, if they sung in ancient times, would have been hesitant with respect to the specific words they used in the song “Words” had they been making a vow. They would most likely have indicated that their song was merely jive talking. Within the Ten Commandments’ framework, words, by attaching them to a vow, created a recourse in the event of a failure one’s perform. Thus, within the scriptural world, all words were not equal, even “equal” itself.

Be well!!

Please like, follow, share or comment.

2 thoughts on “The Power of the Word- Matot’s Ten Commandments’ Moment”